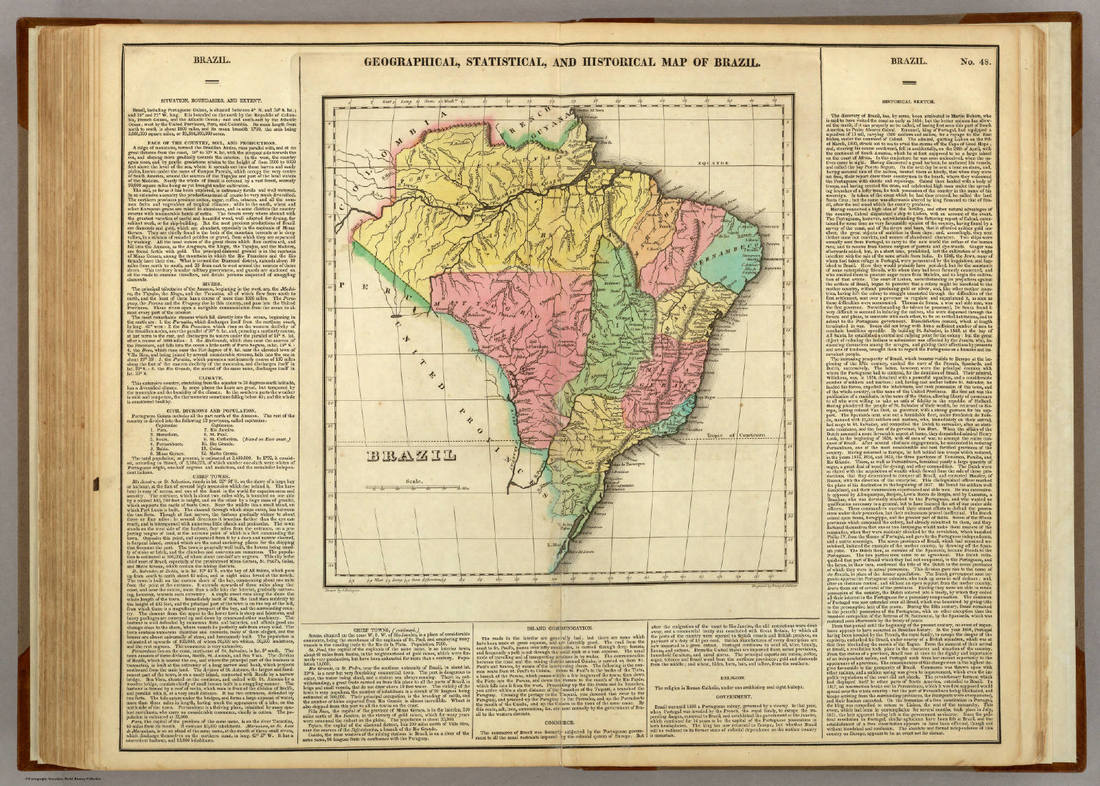

Brazil |

Brazil was a major exporter of coffee throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Coffee was an important driver in stimulating economic development and infrastructure investment within the country.

Connecting the coffee plantations to shipping hubs like Rio de Janeiro and Santos meant lower costs and more competitive advantage in the global markets. Railroads were built across the coffee growing regions of the country between 1860-1900. This expanded the coffee industry, and created secondary opportunities for trading, shipping, and financing. The middle men stationed themselves in cities, like Rio, which helped the region transition into a metropolis. |

|

Coffee plantations made their way through the Javanese countryside and transformed the environment in its wake.

Before 1832, coffee production was restricted to the west side of the region. In the 1830s, though, a series of regulations put in place by the Dutch East Indian Company forced the peasants to set aside certain amounts of land for crops. They were then required to sell the crops back to the government for a fixed, below-market-value price. Coffee production increased from 20,000 tons in 1823 to 80,000 tons in 1840. Peasants had to move further away from their homes to keep up with the demand. Coffee preferred virgin soil, and replanting elderly trees cost too much time and money. They clear-cut forests in order to produce enough coffee to fulfill their contracts with the government. Growing coffee is very harsh on the fields. All existing vegetation is stripped away, as this increases yield initially. Erosion is then amplified, and most nutrients are stripped during heavy rains. With growing practices such as these, the soil can not sustain agriculture very long. Soon, diseases such as leaf rust began to choke out orchards. The Javanese could not cure their trees of this, and by 1880 production had declined steeply. Man hours switch to other, more profitable crops. |

Java |

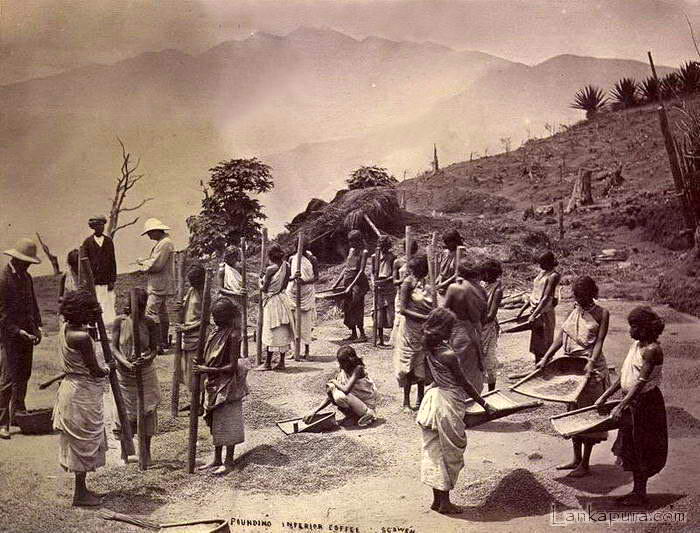

Ceylon |

In Ceylon, coffee production reinforced cultural biases in the communities and marginalized certain groups.

Ceylon was a British colony and provided incentives for European men to move to the region and begin plantations. They were given lower loan rates and other preferential treatment by the government. Indigenous people only controlled a small fraction of the land available for coffee growing. When local labour became scarce, European plantation owners hired head-hunters to bring back migrant labour. These head hunters recruited low caste workers from south India to work seasonally on Ceylon's plantations. In the beginning, they would only recruit men, however it was soon discovered that women could be paid less and could be utilized for the sorting and processing of the beans. Additionally, if the men brought their wives, they were more likely to stay for longer periods of time to work. Between the caste system still ingrained from India, and the patriarchy enforced by both the Europeans and the local people, there was a clear hierarchy within the plantation. Plantation owners used this as a tool to control workers, giving some more power than others. This also divided the work force so that they would never come together to revolt against unfair practices. |

- Clarence-Smith, William and Steven Topic. Clobal Coffee Economy in Africa, Asia and Latin America, 1500-1989. Cambridge University Press, 2003. Online. <http://lib.myilibrary.com/Open.aspx?id=16295>.

- Pendergrast, Mark. Uncommon Grounds. New York: Basic Books, 1999. Print.